The Hindu culture is the life-breath of Hindusthan. It is therefore clear that if Hindusthan is to be protected, we should first nourish the Hindu culture. If the Hindu culture perishes in Hindusthan itself, and if the Hindu society ceases to exist, it will hardly be appropriate to refer to the mere geographical entity that remains as Hindusthan. Mere geographical lumps do not make a nation. The entire society should be in such a vigilant and organized condition that no one would dare to cast an evil eye on any of our points of honour.

Strength, it should be remembered, comes only through the organization. It is, therefore, the duty of every Hindu to do his best to consolidate the Hindu society. The Sangh is just carrying out this supreme task. The present fate of the country cannot be changed unless lakhs of young men dedicate their entire lifetime for that cause. To mould the minds of our youth towards that end is the supreme aim of the Sangh.”

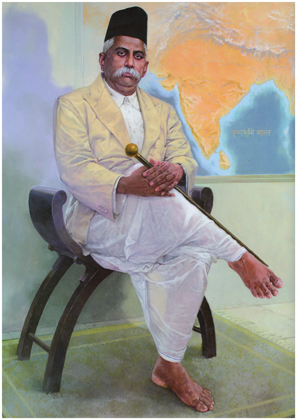

– Dr Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, Founder of RSS

Sangh: Unique and Evergreen

A unique phenomenon in the history of Bharat in the twentieth century is the birth and unceasing growth of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The Sangh’s sphere of influence has been spreading far and wide, not only inside Bharat but also abroad, like the radiance of a many splendored diamond. Sangh-inspired institutions and movements today form a strong presence in social, cultural, educational, labour, developmental, political and other fields of nationalist endeavour. Sangh initiated movements – be they social-reformist or anti-secessionist – evoke ready response and approbation from the common multitudes as well as from vast numbers of the elite of different shades. It has increasingly been recognized that the Sangh is not a mere reaction to one or another social or political aberration. It represents a corpus of thought and action firmly rooted in genuine nationalism and in the age-old tradition of this country.

No other movement or institution has attracted such vast numbers of adherents, several thousands of them making social work their life’s mission, whose character and integrity are not doubted even by their most virulent critics.

As a movement for national reconstruction totally nurtured by the people, Sangh has no parallel in Bharat or elsewhere. The growth of the Sangh – as a movement for the assertion of Bharat’s national identity – acquires added significance when we remember that the birth of the Sangh was preceded by a mental, cultural and economic onslaught by alien rulers for long decades.

There could be only one explanation for the continuing march of the Sangh from strength to strength: The emotive response of the millions to the vision of Bharat’s national glory, based on the noblest values constituting the cultural and spiritual legacy of the land and collectively called ‘Dharma’, comprising faith in the oneness of the human race, the underlying unity of all religious traditions, the basic divinity of the human being, complementarity and inter-relatedness of all forms of creation both animate and inanimate and the primacy of spiritual experience. That the mission of the Sangh is in tune with a millennia-old heritage itself carries an irresistible appeal.

It would have been logical for our post-1947 rulers to re-structure the national life in keeping with our culture. Sadly, that golden opportunity was lost. Until Dharma also is recognized as a basis of survival and progress, national integration and such other oft-repeated goals will remain a far cry indeed. Idealism and patriotism are tangible exterior manifestations of Dharma.

Absence of idealism has been at the root of most problems haunting our polity. Amidst such an environment, Sangh is unique in according primacy to the inculcation of patriotism in all citizens and in all life’s activities. National reconstruction demands the fostering of a national character, uncompromising devotion to the Motherland, discipline self-restraint, courage and heroism. To create and nurture these noble impulses is the most challenging task before the country – what Swami Vivekananda succinctly called man-making.

It is to this historic mission that the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh has addressed itself.

Sangh: A Dynamic Power-House

Great oaks from little acorns grow. What started as a tiny stream in an obscure corner of Nagpur in Maharashtra 92 years ago has now swollen into a mighty river engulfing the remotest villages of the country. That the number of Sangh Shakhas has crossed 57000 is one indicator of the expanding reach of the Sangh.

It redounds to the foresight of Dr Keshav Baliram Hedgewar (1889-1940) that he anticipated the need for strengthening the foundations of the Hindu society and for preparing it for challenges on social, economic, cultural, religious, philosophical and political planes. A galaxy of savants such as Dayananda and Vivekananda, Aurobindo and Tilak, had sown the seeds of the most recent phase of national renaissance. What was needed was a sufficiently strong instrumentality for carrying that process onward. This instrumentality was created and bequeathed to the nation by Dr. Hedgewar in the form of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh which he, after years of deliberate and patient preparation, founded at Nagpur on 27th September, Vijayadashami Day of 1925.

One of the hazards of organisation-building is allowing one’s vision to be clouded with immediate concerns, resulting in dilution of perception of the ultimate goal. Dr Hedgewar’s especial strength was that he never allowed demands of the immediate present to veer him away from the ultimate mission he set to himself.

Keeping aflame the spirit of freedom and endeavouring simultaneously to strengthen the cultural roots of the nation marked the twin features of the character of the Sangh from the beginning, and that has to this day remained its main plank. Every passing day has confirmed the validity of this basic philosophy. Erosion of the nation’s integrity in the name of secularism, economic and moral bankruptcy, incessant conversions from the Hindu fold through money-power, ever-increasing trends of secession, thought-patterns and education dissonant with the native character of the people, and State-sponsored denigration of anything that goes by the name of Hindu or Hindutwa: these pervasive tendencies provide ample proof of the soundness of the philosophical foundation of the Sangh as conceived by Dr Hedgewar and its continued relevance for the survival and health of the Hindu society and of the nation as a whole. It is the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh alone which has consistently been sounding the alarm against all these wrong tendencies in the body-politic of Bharat.

Dr Hedgewar said often, “Even if the British leave unless the Hindus are organised as a powerful nation, where is the guarantee that we shall be able to protect our freedom?” His words have proved to be prophetic. Conjointly with Independence, parts of Punjab, Bengal, Sindh and the Frontier areas were sundered from Bharat; and, four and a half decades after the nation’s attaining freedom, Kashmir remains a thorn in the flesh.

Continuous efforts have been there to make Assam a Muslim majority province. Likewise, no-holds-barred efforts to proselytize by Christian missions continue unabated. Even armed revolt has been engineered (e.g., in Nagaland) to carve out independent Christian provinces. Such activities receive ready to support and unlimited funds from foreign countries and agencies keenly interested in destabilizing Bharat for their own ends.

Sangh’s alone has been the voice of genuine patriotic concern amidst the cacophonous, politically inspired shibboleths of undefined secularism, etc.

Even at the inception, the Sangh was viewed by its founder not as a sectoral activity or movement, but as a dynamic power-house energizing every field of national activity. Antidote to Self-Oblivion

The idea of founding the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh was conceived at a time when self-oblivion had overtaken the society. The struggle for political independence occupied the minds of people; this was but natural. However, what was askew was the tacit assumption that the advent of freedom would automatically usher in a revival of genuine nationalist values which had perforce receded during foreign rule. Looking to the West as the pinnacle of civilization, irrationally perpetuating the Britishers’ self-serving theories of the ‘White Man’s burden’; that the Hindus were ‘a nation-in-the-making’, that the Hindus had achieved nothing of significance in the past, that Westernisation was the only hope for ‘the dying race’ that were the Hindus; unquestioning acceptance of myths floated by Westerners even in the name of history (e.g., that the Aryans came from outside), that life in Bharat was and had always been at a near primitive state; – acceptance of such numerous myths had virtually become mandatory for anyone with the slightest pretensions to education or intellectuality.

That this breed still claims adherents even seven decades after Independence bespeaks the intensity of the overarching colonial legacy.

All the father-figures of the national renaissance from Swami Vivekananda to Lokmanya Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi had laid great stress on the fact that releasing the society from such mental thraldom was as necessary as throwing out the imperialist rulers.

While efforts to hasten political independence were being pursued in various forms, there were few or no sustained efforts for restoration of the Hindu psyche to its pristine form. Indeed, it is the latter which should constitute the content or core of freedom.

Such was the backdrop for envisioning a countrywide movement such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Is it not the lack of social cohesion which enabled a handful of traders and shop keepers (who were no match to us either in intellectual brilliance or physical prowess) to establish their empire here? It was the native chieftains who facilitated the repeated destruction of the sacred Somnath shrine. Wasn’t it Raja Mansingh who, by becoming a kingpin of Akbar’s regime, betrayed the interests of the Hindus?

As if testifying to the sagacity of the proverb ‘The more things change, the more they remain the same’ – considerable sections of the so-called academia and the elite even today display a singular lack of national consciousness even after witnessing such horrendous insult to nationhood as the partition of the country.

The fact that such a breed continues to exist even after so much historical and recent experience provides the strongest raison det’re for intense and continuous propagation of the ideal of nationalism and the recognition of the Hindu national identity as a fundamental fact transcending corroboration and discussion. Any compromise in this regard is bound to cause peril to hard-earned freedom; and without freedom, there will be no prospect of progress for all either. Equally, it is a fact of history that national consciousness should not merely remain an idea or concept, but should be reflected in every single activity of life.

A burning devotion to the Motherland, a feeling of fraternity among all citizens, intense awareness of a common national life derived from a common culture and shared history and heritage – these, in brief, may be said to constitute the life-springs of a nation.

It is these sentiments which have to be instilled in each child. Obviously, this task is beyond the capabilities of political institutions. This is basically a social task. The mechanism Dr Hedgewar evolved for the fulfilment of this all-important task is the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Dr Hedgewar not only had the foresight to anticipate this need, but also the skills of organisation needed to give a concrete shape to that concept.

The Founder:

Keshav Baliram Hedgewar was born on Varsha Pratipada, the Hindu New Year Day, 1st April 1889, at Nagpur. Even as a child he started questioning how a handful of foreigners could for so long rule over a vast and ancient nation like Bharat. No wonder that he threw away the sweets distributed on the occasion of the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria’s coronation. He was eight years old at the time. When studying in high school he started participating in nationalist activities, and, in fact, unfurled the banner of independence during Dusserah at Rampayali in 1907. The intensity of his urge to free the Motherland grew steadily. In 1908, he was expelled from school for leading the students in raising the ‘seditious’ cry of ‘Vande Mataram’. He had to move to Pune to complete his matriculation.

Hedgewar opted for a medical course in Calcutta, chiefly prompted by the prospect of getting first-hand acquaintance with the underground movement. He soon became a core member of one of the leading revolutionary groups called Anusheelan Samiti, and also plunged himself into various social-service activities. When the river Damodar was in floods in 1913, he rushed to join the relief team.

He returned to Nagpur in 1916 as a qualified doctor. However, he did not (indeed never intended to) practice medicine despite dire poverty at home. Remaining a bachelor, he preferred to become a physician to cure the ills of the nation. By then, he had established active contact with stalwarts like Lokmanya Tilak, Dr Munje and Loknayak M. S. Anay. He worked in responsible positions in the Congress and Hindu Mahasabha, till the early 1920s.

Hedgewar’s public speeches of those days were sheer fire and brimstone. It was not long before he had to face court trials. In one such trial, he defended himself declaring, ‘The only government that has a right to exist is a government of the people. The Europeans and those who call themselves the government of this country should recognise that the time for their graceful exit is approaching.’ He was awarded one year’s rigorous imprisonment.

After release from prison, Dr Hedgewar, while continuously immersed in various social and political activities, intensified his quest for an understanding of the true nature of our nation for whose freedom the struggle was being carried on. Political emancipation from the foreign rule alone could not provide the cure for all the nation’s ills.

Bharat is not a nation born recently. It has not only been a nation for millennia but also had made phenomenal progress in science, commerce, arts, technology, agriculture and other spheres, not to mention philosophy and the spiritual domain wherein its achievements continue to elicit wonderment to this day. It is also a fact of history that the cultural empire of Bharat extended to the whole of South-east Asia for over four centuries. Equally, it is a sad fact of history that social disunity and dissension have been the cause of Bharat’s political subjugation by alien invaders.

The 800-year-long resistance of the Hindus to Islamic rule had its own lesson for the British. Seeing that physical repression would not be of much avail, the British, through subtle and not-so-subtle ways, attempted to subvert the Hindu mind itself. They did succeed in part; and a Westward-looking social segment was created, mainly through enforcing the new system of education tailored to generate armies of clerks end ‘brown sahibs’. Needless to say, in such an environment, a cleavage developed between society and its cultural roots and legacy. The nation’s identity became eroded.

It was to such a national self-oblivion that a cure had to be found. The Congress leaders’ policy of appeasement of the Muslims was but one symptom of the malaise. It is an irony of history that – even after paying the ultimate price of vivisection of their cherished motherland – the Hindus have been treated as second-order citizens by successive governments of post-independence Bharat.

This was indeed foreseen by Dr Hedgewar. Years of thinking had convinced him that a strong and united Hindu society alone is the sine qua non for not only the all-round prosperity but for the very survival of Bharat as an independent sovereign nation. Social cohesion alone could ensure national integrity.

Dr Hedgewar’s response to this challenge was the founding of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in 1925. The sweep and amplitude of one great mind can be fully grasped only by minds with a like vision and imagination. Thus, even in the early days of the Sangh, it drew praise and approval from eminent stalwarts including Mahatma Gandhi, Savarkar, Subhash Chandra Bose, Madan Mohan Malaviya and others.

The first Shakha of the Sangh was started with a handful of youth at Nagpur. Gradually, Shakhas sprouted in other provinces. Soon, there were vast numbers of ‘Pracharaks’ (whole-time social workers totally dedicated to nation-building activities) working for the fulfilment of the Sangh mission.

Dr Hedgewar toiled night and day to lay a secure foundation for strengthening and growth of the Sangh. That tremendous work spanning fifteen years did take its toll, and Dr Hedgewar succumbed to illness on 21st June 1940 – at the comparatively young age of 51.

From 1940 onwards, the task of steering the organisation as the second Sar-Sanghachalak came upon the shoulders of Sri Guruji (Madhav Sadashiva Golwalkar, 19.2.1906 – 5.6.1973). He, with his tireless movement all through the year to each and every province meeting the swayamsevaks, inspiring them to put in more time and energy, made the Sangh grow rapidly even up to far-off places in Assam and Kerala. The Sangh which previously had only a few Shakhas in and around Nagpur, Vidarbha, Maharashtra and in some distant places like Lahore, Delhi, Varanasi, Calcutta and Madras began to spread with his inspiring personality at the helm, far and wide, in the highly surcharged prevailing political atmosphere of the country, then struggling for its freedom, with ever-increasing number of Pracharaks submitting themselves for the Sangh work, giving a further fillip to the process. Sri Guruji, with his great erudition, cogently propounded the historical and sociological background, and the logicality of the concept of Hindu Rashtra, which until then was just an empirical thought. He thus widened the ideological base of the Sangh, making it intelligible to a lay villager and the urban intellectual alike. With his uncompromising stress on the one-hour Shakha technique through his own word and deed, he perfected the Sangh methodology also, in every minute detail, thus making it, through proper samskars, an ideal instrument. As more and more co-workers, imbued with Sangh ideology and organisational skill, got ready, with his blessings, one after another organisation (like ABVP BMS, BJS and BKVA etc.) began to branch forth, as and when the circumstances demanded.

In the meantime, after the assassination of Gandhiji, the Sangh also had to – though unjustly and temporarily – pass through the fire-ordeal of a ban, but ultimately it came out totally unblemished and as out of eclipse again continued with its mission. In 1973, after thirty-three years of long and unstinted stewardship, when Sri Guruji passed away, the responsibility was passed on to Sri Balasaheb Deoras (Madhukar Dattatreya Deoras: 11.12.1915 to 17.6.1996) the third Sar-Sanghachalak. In his tenure of twenty years, the growth of the Sangh, apart from geographical spread far and wide, has been meteoric, with leaping numbers of varied service projects and ever-expanding horizons of the Sangh-inspired organizations.

Balasaheb Deoras passed on the baton of Sarsanghchalak to Prof. Rajendra Singh in 1994. He, in turn, delegated his responsibility to K S Sudarshan in the year 2000. In 2009, Sudarshan passed on his responsibility as Sarsanghchalak to Dr Mohanrao Bhagwat under whose leadership the RSS is marching ahead on its way to accomplish its mission and translate its vision of a united, strong, and prosperous Bharat.

The Sangh Methodology

Expressed in the simplest terms, the ideal of the Sangh is to carry the nation to the pinnacle of glory, through organising the entire society and ensuring the protection of Hindu Dharma.

Having identified this goal, the Sangh created a method of work in consonance with that ideal. Decades of functioning has confirmed that this is the most effective way of organising society.

The Sangh’s method of working is of the simplest kind, and there is hardly anything esoteric about it. Coming together every day for an hour is the heart of the technique, and the Sangh has always grown only by personal contact. This is a self-contained mechanism; hence its success.

The daily Shakha is undoubtedly the most visible symbol of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. The Shakha is as simple in its structure as it is grand in conception. No better example can be given to prove the truth of the adage that it takes a genius to simplify a mechanical tool, while even a third-rate engineer can complicate a simple mechanism! After nearly seven decades since the inception of the Sangh, people continue to express puzzlement as to how such a simple tool as the daily Shakha can produce idealists and patriots of such sterling worth, willing to dedicate all their energies and talents to the cause of the Motherland, willing even to shed their lives if need be to protect the honour of the Motherland. Herein lies the extraordinary vision, skill and foresight of Dr Hedgewar, the founder of the Sangh.

What is Shakha?

A saffron flag (called the Bhagawa Dhwaj) flutters in the midst of an open playground. Youths and boys of all ages engage in varieties of indigenous games. Uninhibited joy fills the air. There are exercises, Suryanamaskar, sometimes training in skillfully wielding the “Danda”. All activities arc totally disciplined. The physical-fitness programmes are followed by group singing of patriotic songs. Also forming part of the routine is exposition and discussion of national events and problems. The day”s activity culminates in the participants” assembling in orderly rows in front of the flag at a single whistle of the group leader, and reverentially reciting the prayer “Namaste Sada Vatsale Matrubhoome” (My salutation to you, loving Motherland). The prayer verses, even as the group leader”s various commands are all in Samskrit. The prayer concludes with a heartfelt utterance of the inspiring incantation “Bharatmata Ki Jai”.

This, in outline, is the Shakha of RSS. The participants are the “Sangh Swayamsevaks”.

The Shakha is the most effective and time-tested instrument for the moulding of men on patriotic lines – outreaching by far its physical dimension.

The Shakha process is further strengthened by graded training-camps celled “Sangha Shiksha Varga” at provincial and all-Bharat level, at regular intervals.

The Sangh has popularised the observance of six national festivals of social significance: Varsha Pratipada or Hindu New Year; Hindu Samrajya Dinotsav on Jyeshtha Shuddha Trayodashi, commemorating the coronation of Chatrapati Shivaji; Gurupooja on Ashadha Poornima; Raksha Bandhan on Shravana Poornima; Vijayadashami on Ashwayuja Shuddha Dashami; and Makara Sankranti.

A Sea-Change in Hindu Psyche:

People expressing doubt about the continued survival or growth of an idea like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh were aplenty in the Twenties and later. However, such doubts have, after seven decades, given place to amazement. Such has been the phenomenal growth of the Sangh. Today, there is not a single major field of life which has remained beyond the purview of the Sangh swayamsevaks.

This does not imply that it has always been smooth-sailing for the Sangh. It has had to pass through many adversities. It was twice banned officially by the government – once in 1948 and again in 1975, and each time Sangh came out of the ordeal with redoubled splendour.

The steady growth of the Sangh is in remarkable contrast with many a national or international movement or “ism” which, after an initial flurry, slowly died a natural death or degenerated and changed their form beyond recognition.

But, to say that the Sangh has survived and grown into huge dimensions (true as this is) does not fully convey the dynamism and vibrancy of the Sangh as the biggest and most widespread movement of this kind perhaps in the entire world. A far truer index of the success of the Sangh is the greatly enhanced self-confidence now visible in the Hindu society. This is clearly evidenced by the warm public response which has greeted not only the hundreds of service projects inspired by the Sangh but also the campaigns and movements are undertaken from time to time, such as those for removal of untouchability, re-invoking the Swadeshi spirit (Swadeshi Jagaran Abhiyan), etc. The support that Sangh-inspired causes like “Save Kashmir” and restoration of Ramajanmabhoomi have been attracting from laymen and intelligentsia alike is a further vindication of the soundness of the Sangh”s approach to issues of national concern.

Gone are the days when Hindu society could be denigrated by all and sundry; gone too are the days when heaping contempt on Hindu society by one ruse or another was equated with intellectual superiority. It is these latter types of pseudo-intellectuals who are now running for shelter. And the more pragmatic among them have now coolly adopted the vocabulary.

Sangh-inspired Organisations

After the advent of Independence in 1947, the centuries-long struggle for freedom gave place to the task of nation-building precisely in a literal sense. But the crucial question was what should be the goal and the means to achieve it. It was here that the men then at the helm stumbled. They had all along been. While engaged in the freedom struggle equating the mere transfer of power from the alien rulers, with real independence and hence to some extent, were bewildered at the sudden turn of circumstances in which they were empowered with authority to rule.

In fact, for them, it was a God-given historic opportunity to shape the destiny of the nation, which was as it was taking a new birth altogether. The real need then was to identify the character and the time-tested basic values, which this ancient nation stood for millennia, and to reshape the nation on that basis with any modifications suited for the changing needs of the day. But they deemed economic progress and material welfare as the finality of an independent nation.

They had before them two models, both from the West. While the American one had in it the capitalist economy with all-permissive individual freedom, which in fact was eating into the very vitals of her social life, the Russian socialist alternative with its ambitious five-year plans, presented a facade of heaven on the earth, in which actually the individual was but a cog in the wheel. Being enamoured by both, and material progress alone being made the touchstone, the new rulers opted to simultaneously ape both – an exercise which ultimately tended to make the nation a carbon copy of neither.

The thinking of the Sangh in this regard has all along been of a very basic nature. From its inception, the goal before the Sangh was to attain the “Param Vaibhav” (the pinnacle of glory) of the Hindu Rashtra, the freedom from the alien rule being just a step in that direction. The transfer of power can at the most be “Swaraj” (one”s own rule) but definitely not “Swatantrya” (actualisation of one”s own potential being). The concept of “Param Vaibhav” has ingrained in it the material progress too of the nation, but not with its very identity and interests mortgaged.

The Sangh with its total commitment to the actualisation of “Swa”, in other words, the Hindu ethos, keeping itself away from the powers-that-be, from 1947 onwards, began on its own to extend its influence to varied fields of social life. The Sangh “Pratijna” (pledge), which until then was for the liberation of the Hindu Rashtra, was amended to indicate “Sarvangeena Unnati” (all-round development) of the nation. The entire gamut of social life was planned to be designed on the rock-bed of Hindu nationalism. The swayamsevaks with the insight and the organisational skill they acquired through the “samskars” on the “sanghasthan” and with the uncompromising urge for the national reassertion gradually began to enter one after another field of national life. The process commenced as early as in the end of forties and has in these four decades encompassed a vast number of areas that the society is composed of.

In 1948, after the assassination of Gandhiji, when the Sangh was unjustly banned, the exuberant student and youth force, which until then was active in the Shakha work only, was mobilised to contact the public with issues of national interest, particularly the draft constitution which was then being debated in the Constituent Assembly. This movement, the Akhil Bharateeya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), in course of time has grown into a massive nation-wide student organisation, successfully harnessing the buoyancy, time, intelligence, talent and creativity in the students, over and above their educational responsibilities, for nation-building activities. Today ABVP is recognised as the front-rank student organisation with a totally nationalist outlook.

Earlier, when most of the Sangh functionaries were unjustly incarcerated, and baseless canards against Sangh were let loose by the establishment, to set the record straight, apart from the “Organiser” weekly in English, a series of language periodicals like “Panchajanya”, “Yuga Dharma” (both Hindi), Vicrama (Kannada) etc., were started. Nowadays, with regard to this fourth estate of democracy, almost all the provinces have their own vernacular papers all belonging to Sangh school of thought and command a very wide range of readership.

The educational system initiated by Macaulay with the motive of producing an army of “brown-skinned Englishmen”, to serve the imperial administration as “the most obedient servants” was another legacy of the British rule in Bharat. After Independence, there was dire need to reshape the entire system. In 1952, the first “Saraswati Shishu Mandir” (nursery school) was founded in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, as an attempt towards inculcating, along with mandatory academic knowledge, discipline, patriotic outlook, love for mother tongue, high moral values and Hindu principles the thrust of education being based upon a holistic approach to the physical, intellectual, moral and spiritual growth of the pupil. The small sapling of this “Shishu Mandir” – which it was in the fifties – has now grown into, a mighty banyan tree as “Vidya Bharati”, an umbrella body for thousands of educational institutions, ranging from nursery to post-graduation level. The system of education being evolved by Vidya Bharati is based on age-old Hindu values, hut having an outer structure in consonance with present-day needs of modern education.

The systematic alienation of the tribals, inhabiting remote forest areas, but who form an inseparable part of the Hindu society through proselytization was another grave challenge that demanded immediate corrective measures. Far away and hence uncontaminated by the sophisticated modernity, they are yet, though deprived of literacy, committed to their own rustic cultural moorings and also are very talented. They had all along been a most exploited lot and easy prey for unscrupulous conversion by Christian missionaries. It is to counter this twin menace of British legacy, that the Bharateeya Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram (BKVA) was founded in the early fifties. The BKVA, now spread over a hundred districts in 21 States, has been striving for the all-round development of the vanavasis, in their own natural surroundings, enabling all their latent potentialities and talents to blossom. Over the decades, the Ashram has succeeded not only in putting a stop to conversions in all its areas of operation but also in bringing the converts back to the Hindu fold.

The trade union movement guided by the alien socialist and Marxist philosophy, started in the thirties, was gaining ground by the time and British left the country. This philosophy, with its faith in class conflict and its methodology of anti-production strikes, was in fact, both in theory and practice, a negation of labour and national interests. Bharateeya Majdoor Sangh, a totally new labour movement, apolitical in character, based on Hindu tenets, was started in 1955. The BMS believes in conciliation whenever a dispute arises and considers strike as the last resort. It does fight against exploitation in any form from whichever party and upholds the all-comprehensive interest of the society as a whole with supreme concern. It is now recognised as a leading labour organisation even at the international level and in the home-front, the second biggest one, far ahead of other similar organisations with socialist and Marxist leanings.

While the Sangh was by itself effective in organising the Hindus and inculcating in them healthy “samskars” like discipline and social consciousness, the need for Vishwa Hindu Parishad began to be felt in the sixties, for augmenting certain grey areas of the activities of the former. For example, there was a need to organise overseas Hindus residing in about 150 countries and provide them with necessary arrangements for upholding their Hindu samskars and faith in their daily lives. There was also a need to bring all sadhus sannyasins and orthodox mathadhipatis on a common platform so that their combined influence could be channelized for the common good of the entire Hindu society. A mechanism to reconvert all those who had been knowingly or unknowingly proselytised to alien faiths and are now desirous of coming back to the Hindu fold was needed. The VHP was founded in 1964, to fill this need.

The VHP is now spearheading the movement to rebuild the temple at Sri Ramajanmabhoomi at Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh. After a four-centuries-long physical struggle fought by the Hindus, a period in which as many as seventy-six battles were fought to recapture the premises, where once stood a beautiful temple, which was desecrated by the Moghul invader Baber, the VHP has now picked up the gauntlet to rebuild the temple, yet more magnificently, at the same spot, whatever be the price in terms of sweat and blood. The first phase of this renewed struggle was won in 1986, when the temple-door, which was unlawfully locked by the government to spite the Hindus, was thrown open to the public by a court order. Again in 1989, the VHP could successfully accomplish the “Shilanyas” of the proposed temple (foundation-laying ceremony), in spite of the numerous hurdles, legal and administrative, and in the teeth of bitter opposition from all those opposed to the project for their own Ulterior motives. The very next year, literally lakhs of Hindus from all over Bharat stormed Ayodhya in a bid to stars “Kar-seva” (rendering physical service as an expression of their devotion), braving the hurdles caused by a hostile government, and successfully hoisted the Bhagawa Flag atop the disputed edifice. There was an unprecedented bloodbath. The VHP is committed to undo the historical insult to the last nuts and bolts and it is this determination of the VHP that has instilled a spirit of righteous militancy in the Hindu society.

With the end of the British raj, Bharat became a democratic republic with a constitution of its own, when the need for a strong political alternative to the ruling party with unalloyed nationalism arose. The Sangh, though it preferred to remain apolitical, was well aware of its commitment to social transformation, including in the political field, based on Hindu values. In fact, politics was and has been wielding all-pervading influence over each and every other field of social life; and as such there was a need to evolve a totally new political culture in the country. It was in that contest that a few senior Sangh functionaries, driven with the uncompromising commitment to Hindu nationalism, decided to form Bharateeya Jan Sangh in 1951, under the presidentship of Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee. The party, apart from electoral battles, had been waging many a political fight for upholding the nation”s integrity and honour. It was in the forefront of the “Save Kashmir” movement in 1952 and also in the movement against the formation of Muslim-dominated Malappuram district in Kerala in 1969.

Having firmly established its foothold on the political arena for over twenty-five years, BJS became the strongest constituent in the Janata Party, which assumed power at the centre in 1977, on a common forum of the linen existing opposition parties. Unnerved with the growing political cloud of BJS, when the other constituents made the very membership of Sangh a bone of contention in the Janata Party, the swayamsevaks came out of that party and formed the Bharateeya Janata Party (BJP) in 1980. This new party continued the legacy of the BJS, with “Integral Humanism” propounded by late Deendayal Upadhyaya as its philosophical base. The BJP, without bothering about its being isolated from other political parties, has been in the vanguard of the movement for Sri Ramajanmabhoomi and also, as a major party, has opposed the move for transfer of Tin Bigha over to Bangladesh. Their differences apart, even the opponents of the BJP accept that it has initiated a totally new political culture. After the general elections of 1991, the party has become the main opposition at the centre and is ruling in four States.

As early as in 1936, Srimati Lakshmibai Kelkar (Mauseeji) of Wardha was prevailing upon Dr Hedgewar that just as men were being trained in Sangh, women too needed to be trained in nationalism and proper samskars. After many months of discussion, Dr Hedgewar, in the end, promised to extend all help to Mauseeji, to found Rashtra Sevika Samiti, an exclusively women”s organisation, its goal being the same as that of Sangh but which was called upon to operate parallel to the latter and with a different name, prayer and independent structure.

The above is a brief, illustrative account of just a few among the vast number of organisations inspired by the Sangh, generally looked Upon as “Sangh Pariwar”. The “Pariwar” in fact is very vast since no field of activity is beyond the reach of Sangh swayamsevaks, and as such a description of each and every activity is beyond the scope of the present book. The swayamsevaks, in whichever field they entered, with their invincible drive to translate their dream of “Sarvangeena Unnati” have made it vibrant with Hindu nationalist ethos. Thus, what was started as a humble man-making activity in the form of Sangh Shakha, in a brief span of seven decades, especially after the advent of Independence, has now assumed the form of a unique and mighty nation-building instrument, with its benign influence pervading each and every field of social life.

Sanghs March: Some Thrust-Areas

The Sangh has often been misrepresented by its detractors, political or ideological, as having political motives or as a para-military organisation. The seven-decades-long growth of the Sangh and its ever-growing influence over the society are also sometimes attempted to be evaluated in political terms. But the Sangh, it must be remembered, is for attaining the “Saravangeena Unnati” (all-round development) of Bharat, and for this end only the swayamsevaks pledge to dedicate themselves. They do desire that the political field too needs to be cleansed and reformed, based on Hindu values and ethos, but politics is just one among the many facets of social life. As such, to cast political aspersion on Sangh is, to say the least, baseless, since the concept of all-round development encompasses the entire spectrum of life, including politics. The Sangh has to its credit a few thousands of service projects, covering varied fields of social life. Apart from the projects, the swayamsevaks on their own are rendering service to the society, individually and collectively too, wherever needed, whatever the cause. In fact, a Sarvodaya leader, in appreciation of the service rendered by the swayamsevaks for the cyclone-hit victims of Andhra Pradesh in 1977, meaningfully said that “RSS” stood for “Ready for Selfless Service”.

Obviously, the real purpose of the Sangh is rightly understood by the unbiased and discerning analyst only.

The thrust of all samskars in the Shakha, though it outwardly appears to be for military-like discipline, which in any case is essential for any nation-building exercise, is for imbibing the noblest qualities of head and heart. Admittedly, a Swayamsevak attending a Shakha is a common man, with exposure to unhealthy and corrupt practices now rampant in the society outside the Sanghasthan. Yet, by involving himself in all the wholesome physical and intellectual programmes, both formal and informal, in the Shakha, he in course of time becomes broadminded and service-oriented, ready to serve the society. In the Shakha, because of his interaction with the other members of society, his angularities become rounded off, the tastes and the outlook get moulded for a purer plane where, in place of self-aggrandizement, the dedication for the service of the society becomes his fervent preoccupation. With these samskars rooted deep in his mind, while he considers participating in daily Shakha, a must in his routine – for that alone provides him with the driving force for all his social work – he gets real satisfaction in applying all his energies for the amelioration of social maladies.

The Shakha, in fact, is not an end in itself, but just a means to achieve the end, which in brief is social transformation. The programmes in the Shakha are so structured that while they develop a proper insight and make one aware of the deficiencies and drawbacks in the society, it also instils a sense of pride and intense love for its glorious cultural heritage and, simultaneously, awakens his commitment to work for his emancipation. Thus, through the instrumentality of the Shakha, men are moulded, and they, in turn, enter varied social fields to ennoble them with Hindu fervour. Just as the pureblood flows out of the heart, to reach each and every body-cell, taking along with it oxygen and nourishment, purging it of its dross, making it function properly and then returning back to the heart to get itself once more energised, the swayamsevaks also imbibe proper samskars in the Shakha, and then propel themselves into diverse social activities.

The aim of the Sangh is to organise the entire Hindu society, and not just to have a Hindu organisation within the ambit of this society. Had it been the latter, then the Sangh too would have added one more number to the already existing thousands of creeds. Though started as an institution, the aim of the Sangh is to expand so extensively that each and every individual and a traditional social institution like family, caste, profession, educational and religious institutions etc., are all to be ultimately engulfed into its system. The goal before the Sangh is to have an organised Hindu society in which all its constituents and institutions function in harmony and co-ordination, just as in the body organs. While this is easily perceived at the conceptual level, the institutional outer form of the Sangh is also necessary for internalisation of this habit of organised living, but without making it a creed.

The swayamsevak considers the Hindu society itself as “Janata Janardana”-God incarnate. Any service rendered to this society, accepting nothing in return, is for him the worship of his god, the “Samaja-roopee Parameshwar! (God in the form of the society). To him, who feels intensely for the good of the society, it provides any number of opportunities of service. The abject poverty, illiteracy, caste barriers, false sense of high and low, untouchability, exploitation, lack of medical facilities, etc., are, to name just a few, the social maladies which call for immediate corrective steps. The prime concern of the swayamsevaks all over the country is now for such service activities. At the Shakha level, a strong orientation is now given for this purpose.

It is but natural that in a self-oblivious society like ours the innate oneness and the fraternal bonds are the first casualty. As such, the poor, the illiterate and the weaker sections in the society become an easy prey for exploitation and conversion to other faiths. While the unsympathetic rich try to suck the blood of the poor, the crafty intelligent exploit the gullible. So, apart from rendering positive service, the swayamsevaks consider it equally important to combat such injustices, on behalf of the weaker sections. Militancy and intolerance become good traits when they are put to use for helping the innocent and the weak in the society. The Bharateeya Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram, the Grahak Panchayat, the BMS, the BKS (Bharateeya Kisan Sangh) etc., are all spearheading such movements for social justice whenever the need arises.

In a society divided on caste, class and language lines, the greatest service from a social worker to his community will be to keep intact the very social fabric. The oneness of the society being an article of faith with the swayamsevak, it becomes all the more important for him to strive for social consolidation, especially when the self-seeking politicians try to drive a wedge between diverse groups for their own selfish ends, and anti-social elements take advantage of such sensitive situations. The unifying Hindu appeal generated by Sangh has always acted as a powerful antidote to the disintegrating pulls exercised by separatist elements, in many a trying situation of conflicts born out of casteism, untouchability and sectarianism. The Rashtriya Sikh Sangat, the Samajik Samarasata Manch of Maharashtra, the “Speak Samskrit” movement of Karnataka, and the like have been rendering yeoman service in this direction.

While founding the Sangh, Dr. Hedgewar – himself a freedom fighter had before him the goal not only of independence, but also of “swatantrya” in its literal sense, i.e., the blossoming of “swa”- the national identity – in every walk of our social life. As such, it has always been the supreme concern of the swayamsevaks, to uphold and seek re-assertion of the national honour wherever it is at stake.

The State of Jammu & Kashmir, with its oppressive Muslim-majority character, has been a headache for our country ever since Independence. The forces inimical to Bharat never wanted Kashmir to integrate itself with Bharat, and in October 1947, immediately after Independence when Pakistan s forces invaded Kashmir, these elements conspired with the enemy to defeat every move to save the situation from our side. However, thanks to the timely collaboration of the entire Sangh force then present at Jammu with the Armed Forces of Bharat, Kashmir was saved. Had it not been for the premature and insensible cease-fire declared unilaterally by our own government, even while a large chunk of our territory was still under the siege of the enemy, our Armed Forces would then itself have driven out the later completely beyond the borders and there would not have been this problem of “Pakistan-occupied Kashmir” (POK), which even now continues to be a scourge undermining the sovereignty of Bharat.

The problem of Kashmir, in fact, is one of our own makings, since, keeping in mind its unique demographic character, unlike other States, it has been conferred a special status under Article 370 of the Constitution, even after its total accession with Bharat. In 1952, Bharateeya Jan Sangh and Praja Parishad, in those days the political front of the Sangh in Jammu & Kashmir Stale, jointly agitated against this special status; and the BJS had to pay a heavy price in the death of Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, the founder-president of the party, in Srinagar jail. He died under dubious circumstances, after being incarcerated there for having led a batch of satyagrahis defying the ban on his entry into the State. However, because of this agitation, the game plan of the conspirators which Sheikh Abdullah as the kingpin, after being exposed, was thwarted and Kashmir was once more saved, for the time being.

The endless appeasement of the Muslim population, especially in Kashmir, practiced by the successive governments at Delhi, has been the bane of our government”s Kashmir policy. Just as too much mollycoddling and lack of discipline spoil the child, so has been Kashmir, a problem created out of our own folly. With about one-third of the State territory illegally occupied by Pakistan, a hostile neighbour, the alienated area has virtually become a haven for subversives. Knowing fully well that open war with Bharat may prove too costly and also with chances of winning unpredictable, Pakistan is waging a cold war, abetting the militants, supplying them with arms, training them for armed revolt from within.

The militants are taking advantage of the government”s weakness, being sure that government dares not take ruthless action against them because of their privileged “minority” tag. They have resorted to all types of inhuman measures to evacuate the minuscule Hindu population from the Valley. They went to the extent of openly burning the national flag at Lal Chowk in Srinagar on an Independence Day. It was the ABVP which first accepted the challenge from the Kashmir militants, and took a massive l0,000 – strong contingent of students from all over the country to Lal Chowk to hoist the tri-colour there. The attempt, however, was foiled by the then government under V.P. Singh. Two years later, the BJP picked up the cue and a historic “Ekta Yatra” (Unity March) from Kanyakumari to Srinagar, with Dr Murli Manohar Joshi the party president himself as the leader, was organised. This 25,000 km-long Yatra successfully culminated at Lal Chowk, exactly on the decided day, braving all the challenges, political as well as others, and did hoist the national tri-colour there, thus proclaiming to the enemy within and without that a competent party had arrived to settle the account.

Apart from the Kashmir issue, the Sangh has all along been in the forefront in each and every national campaign, be it “Ban Cow-slaughter” campaign of 1952 or the mass collection drive for the Vivekananda Rock Memorial at Kanyakumari in 1963. The Ekatmata Rath Yatra of Ganga Jal and Bharatmata in 1983 and the later issue of Ramajanmabhoomi temple, sponsored by the Sangh Pariwar, have irrefutably established that the Hindu society would respond like a “Virat Purush” (one corporate body), when the innate chord of Hindusthan is stimulated to pulsate in every Hindu heart.

Thus the thrust of the Sangh and its methodology is not restricted to its outward institutional form only, but is multi-dimensional, extending beyond the boundaries of “sanghasthan” . The aim is to activise the dormant Hindu society, to make it come out of its self-oblivion and realise its past mistakes, to instill in it a firm determination to set them right, and finally to make it bestir itself to reassert its honour and self-respect so that no power on earth dares challenge it in the days to come.

Toward The Hindu Century

Not only the context of Bharat but also the global situation re-confirms the validity of the philosophical foundation of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

That the coming or twenty-first century will be a century dominated by Hindutwa and what it stands for is a prophecy which has been heard from many quarters including eminent historians.

What is the state of the world on the eve of the twenty-first century?

The materialist approach to life which has been honed to perfection from the 16th to mid-20th century appears to have now run its course. Aggressive industrialism has proved its own undoing; the life-style and institutions based on such a philosophy no longer seem viable; America now finds itself driven to resorting to open wars in desperation, in order somehow to secure a further lease on the world”s resources which it has been recklessly consuming. At the other end of the spectrum was communism which had started as a reaction to the downgrading of man by capitalism, but has now itself walked into the capitalist mansion – after 70 years of experimentation in the Soviet Union and 50 years in China. In the name of socialism, China has accepted modern monopoly capitalism.

The capitalist and communist ideologies alike base themselves on postulates such as survival of the fittest, unlimited exploitation of nature, unhindered individual right, and struggle as the normal pattern of existence.

While the Marxist vision has crumbled even in its home-ground, the capitalist system is on its last throes, gasping to survive as a secluded archipelago of half a dozen islands of physical prosperity. The world is looking for a viable and universally acceptable life-vision. It is Hinduism alone which is in a position to provide such a vision.

The West views the world as made up of different parts functioning according to certain rules and patterns. In contrast, Bharat has always recognised mutual interdependence and complementarily as the basis of life, and a symbiotic relationship between man and nature. Man is regarded by Hinduism not as a separate creature superior to the rest of creation, but as a part and parcel of the whole. The validity of this philosophy has gained added credence in the last quarter of the twentieth century and has found votaries far beyond the borders of Bharat.

The proclamation that the coming century will be the Hindu Century is thus not a chimaera but based on hard facts, analysis and prospects.

Panacea: Cultural Rejuvenation

Economic ideologies governing present policies have proved to be unworkable, not merely because of implementation level aberrations as frequently argued, but because of basic flaws and wrong assumptions. For instance – supply, demand, and market mechanisms have been regarded as the basic parameters of economics. Adherence to this mindset has resulted in fast depletion of natural resources on the one hand, and, on the other, a physically elusive and morally indefensible life-style. In contrast, the Hindu view of life has always advocated living in harmony with nature; such harmony desiderates voluntary restraint on consumption. A corollary of this basic premise is that self-restraint is not only inevitable for practical reasons, but also a source of universal joy and a stepping-stone for spiritual evolution.

The relevance of this conservationist approach is now being increasingly recognised by progressive economists in many parts of the world.

It is the neglect of these basics which has driven countries like Bharat to the brink of bankruptcy and the West to regressive colonialist strategies.

That the rubric of Dharma should be reflected in all facets of life is a founding principle of Sangh. A constant endeavour of Sangh and all its offshoots has been the propagation of Hindu values as the guiding principles in all sectors ranging from education to labour, sociology to economics.

Obsession with West-originated theories has resulted in blinkered vision in major knowledge-areas like history, science, technology, economies, administration, etc. Thus, mainstream economics as taught and practiced today is blissfully unaware of the fact that such nuances as real commodity prices were comprehensively dealt with by Shukracharya, Kautilya and other sages. The materialist approach, blindly copied from the West, has led the country downhill. While Independent Bharat started with a balance of Rs. 18,000 crores, the Bharat of 1992 is in debt to the tune of Rs. 4,00,000 crores. The so-called “industrial Revolution”, supposed to have led to the prosperity of the West, was made possible from the post-Plassey loot from Bharat. With no such plundered capital, Bharat obviously could not reach the heights of material progress scaled in the West. This externally induced impoverishment has been used by the West to make Bharat a debtor country. However, what should cause greater concern is the culturally-induced poverty in the psyche of the people through endlessly repeating “you are poor”, “you are backward”, and ‘you are primitive”.

The need is to recreate the self-confidence of the people of Bharat. Not so long ago, Bharat produced such superior yarn that Britain had to ban the sale of textiles from Bharat. Likewise, Bharat produced the best steel in the world costing as little as Rs. 50 per tonne, while the “advanced” West produced inferior steel at Rs. 250 per tonne.

That the indigenous science and technology of Bharat were deliberately crushed by the West is undisputed. Curiously, the same colonialist intervention from the West continues even on the eve of the twenty-first century, now in the form of GATT, World Bank and IMF conditionality, “Structural Adjustment”, “Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty”, etc. While political independence was attained in 1947, a major and sustained struggle for economic independence appears warranted as we approach the golden Jubilee Year of political emancipation of Bharat.

A lasting solution to the economic crisis can come only from cultural rejuvenation and re-assertion of Hindu values such as reverence for man and nature, a non-acquisitive and non-exploitative life-pattern, recognising mutuality rather than the individual right as the basis of the economy, voluntary austerity in consumption, and a premium on self-reliance. Sangh has been propagating this value-system based on self-knowledge and self-control, not merely because it is necessitated by the present state of the world, but even more basically because it is a source of individual joy, social harmony, cultural richness, spiritual advancement and universal peace.